Apple Pulls Meta’s WhatsApp and Threads From App Store in China After Government Order

Apple Inc. said that it removed Meta Platforms Inc.’s WhatsApp and Threads from its China apps store after an order from the country’s internet regulator, which said the services pose risks to the country’s security.

The order comes on the heels of a cleanup program Chinese regulators initiated in 2023 that was expected to remove many defunct or unregistered apps from domestic iOS and Android stores. The action against the American tech services comes as the U.S. government is taking steps toward a ban on TikTok, the hit video app from Beijing-based ByteDance Ltd. U.S. politicians have also cited national security concerns in their push to force the company to either sell TikTok to a non-Chinese owner or face a ban in the U.S. market.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]“We are obligated to follow the laws in the countries where we operate, even when we disagree. The Cyberspace Administration of China ordered the removal of these apps from the China storefront based on their national security concerns,” Apple said in a statement. “These apps remain available for download on all other storefronts where they appear.”

Foreign social media platforms like WhatsApp were already largely inaccessible from China without tools to circumvent Beijing’s Great Firewall, such as virtual private networks. The removal of these apps will make it more difficult for users within the country to view content on these international platforms.

In August, China asked all mobile app developers to register with the government by the end of March, a move that Beijing painted as a bid to counter telephone scams and fraud. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology said that it would carry out supervision work on those filings from April to June, and to take action against apps that were not registered. App developers would also be required to set up and improve mechanisms to handle “illegal information.”

The MIIT move was another step by Beijing to tighten controls across its cyberspace, forcing domestic and foreign companies to block off information considered politically sensitive. Beyond apps, websites and large language AI models have also been subject to greater content curbs.

China’s action comes as TikTok divestiture legislation is expected to be included in a fast-moving aid package for Ukraine and Israel that Congress is expected to vote on this Saturday.

The Wall Street Journal was first to report the removal. A Meta spokesperson referred Bloomberg News to Apple’s statement.

China is a key nation for the iPhone, its largest consumer market outside the U.S. and its primary production base. Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook visited the country earlier this year and emphasized its importance to his business. Apple has long said that it needs to follow local laws as part of operating its app store effectively in different countries.

Source: Tech – TIME | 19 Apr 2024 | 4:50 pm

How AI Is Wreaking Havoc on the Fanbases of Taylor Swift, Drake, and Other Pop Stars

In the last week, highly anticipated songs by Drake and Taylor Swift appeared to leak online, sparking enormous reactions. Massive Reddit threads spawned, dissecting musical choices. Meme videos were created simulating other rappers’ reactions to being dissed by Drake. The rapper Rick Ross even responded to the song’s bars about him with a diss track of his own.

But there was one big problem: neither Swift nor Drake confirmed that the songs were real. In fact, loud contingents on social media claimed that the songs were AI-generated hoaxes, and begged fellow fans not to listen to them. Fervent fans soon became engulfed in rabid hunts for clues and debates aimed at decoding the songs’ levels of authenticity.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]These types of arguments have recently intensified and will only continue ballooning, as AI vocal clones keep improving and becoming increasingly accessible to everyday people. These days, even an artist’s biggest fans have trouble telling the difference between their heroes and AI-creations. They will continue to be stymied in the coming months, as the music industry and lawmakers slowly work to determine how best to protect human creators from artificial imposters.

The Advent of AI Deepfakes

AI first shook the pop music world last year, when a song that seemed to be by Drake and the Weekend called “Heart on My Sleeve” went viral, with millions of plays across TikTok, Spotify, and YouTube. But the song was soon revealed to have been created by an anonymous musician named ghostwriter977, who used an AI-powered filter to turn their voice into those of both pop stars.

Many fans of both artists loved the song anyway, and it was later submitted for Grammys consideration. And some artists embraced new deepfake technology, including Grimes, who has long experimented with technological advancements and who developed a clone of her voice and then encouraged musicians to create songs using it.

But soundalikes soon began roiling the fanbases of other artists. Many top stars, like Frank Ocean and Beyoncé, have turned to intense policies of secrecy around their output (Ocean has carried around physical hard drives of his music to prevent leaking), resulting in desperate fans going to extreme lengths to try to obtain new songs. This has opened the door for scammers: Last year, a scammer sold AI-created songs to Frank Ocean superfans for thousands of dollars. A few months later, snippets that purported to be taken from new Harry Styles and One Direction songs surfaced across the web, with fans also paying for those. But many fans argued vociferously that they were hoaxes. Not even AI-analysis companies could determine whether they were real, 404 Media reported.

Read More: AI’s Influence on Music Is Raising Some Difficult Questions

Drake and Taylor… Or Not?

This week, AI shook up the fanbases of two of the biggest pop stars in the world: Taylor Swift and Drake. First came a snippet of Drake’s “Push Ups,” a track that seemingly responded to Kendrick Lamar’s taunts of him in the song “Like That.” (“Pipsqueak, pipe down,” went one line from “Push Ups.”) The track, which also took aim at Rick Ross, The Weeknd, and Metro Boomin, quickly went viral, and Ross fired back a diss track of his own.

But the internet was divided as to whether or not the clip was actually made by Drake. The original leak was low quality; Drake’s vocals sound grainy and monotone. Even the rapper Joe Budden, who hosts the prominent hip-hop podcast The Joe Budden Podcast, said that he was “on the fence” for a while about whether or not it was AI.

A higher quality version of the song was subsequently released, leading many news outlets and social media posters to treat “Push Ups” as a genuine Drake song. Strangely enough, Drake has toyed with this ambiguity: He has yet to claim the song as his own, but posted an Instagram story containing people dancing to parts of it. Whether or not he made it, the song has become an unmistakable entry in a sprawling rap beef that has taken the hip-hop world by storm.

“Push Ups” has a reference to Taylor Swift: It accuses Lamar of being so controlled by his label that they commanded him to record a “verse for the Swifties,” on the 2015 remix of her song “Bad Blood.” On Wednesday, Swifties went into a frenzy when a leaked version of her highly anticipated new album, The Tortured Poets Department, began making the rounds online two days before its release date. Purported leaks have been popping up for months, including some that were eventually debunked as AI-generated. Given all of the false trails across the web, many Swift fans dismissed these new leaks as fake as well. But the songs are also being treated as real by many fans on Reddit, who are already announcing their favorite tracks and moments a day before the album’s official release.

Read More: Everything We Know About Taylor Swift’s New Album The Tortured Poets Department

listened to TTPD leaks and genuinely it’s so funny that even her fans can’t tell if it’s AI or not. pretty sure they were real tracks but just the fact that her own stans were in denial tells me everything I need to know about the root of the love for her artistry

— mina 🤹🏽♀️ (@tectonicromance) April 18, 2024

Can the music industry fight back?

Some of these vocal deepfakes are not much more than a nuisance to major artists, because they are low-quality and easy to detect. AI tools often will get the timbre of a distinctive voice slightly wrong, and can glitch when artists use melisma—sliding up and down on a single syllable—or suddenly jump registers. Some pronunciations of lyrics also come out garbled, or with a slightly wrong accent.

But AI tools are constantly improving and getting closer to the real thing. OpenAI recently shared a preview of Voice Engine, their latest tool that generates natural-sounding speech mimicking certain speakers. Researchers and AI companies are racing to create voice clone detection software, but their success rates have been uneven.

So some musicians and music labels are fighting back with the avenues they have available to them. Three major music publishers—Universal Music Publishing Group, Concord Music Group and ABKCO—sued the AI company Anthropic, alleging that the company infringed on copyrighted song lyrics. More than 200 musicians, including Billie Eilish, Stevie Wonder, and Nicki Minaj, recently signed a letter decrying the “predatory use of AI to steal professional artists’ voices and likenesses.” And BPI, a UK music industry group, threatened legal action against the vocal cloning service Jammable.

The music industry has growing support from lawmakers. Last month, Tennessee governor Bill Lee signed into law the ELVIS Act, which prohibits people from using AI to mimic an artist’s voice without their permission. And U.S. senators announced a similar bill called the NO FAKES Act. “We must put in place rules of the road to protect people from having their voice and likeness replicated through AI without their permission,” Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar wrote in a statement.

It will likely take a long time for this bill or other similar ones to wind their way through the halls of Congress. Even if one of them passes, it will be exceedingly hard to enforce, given the anonymity of many of these online posters and the penchant for deleted songs to pop back up in the form of unlicensed copies. So it’s all but assured that deepfaked songs will continue to excite, confuse, and anger music fans in the months and years to come.

Source: Tech – TIME | 19 Apr 2024 | 8:04 am

Google Fires 28 Workers Involved in Protests Over $1.2 Billion Israeli Contract

Alphabet Inc.’s Google fired 28 employees after they were involved in protests against Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion joint contract with Amazon.com Inc. to provide the Israeli government and military with AI and cloud services.

Read More: Google Contract Shows Deal With Israel Defense Ministry

The protests, which were led by the No Tech for Apartheid organization, took place Tuesday across Google offices in New York City, Seattle, and Sunnyvale, California. Protesters in New York and California staged a nearly 10-hour sit-in, with others documenting the action, including through a Twitch livestream. Nine of them were arrested Tuesday evening on trespassing charges.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Several workers involved in the protests, including those who were not directly engaged in the sit-in, received a message from the company’s Employee Relations group informing them that they had been put on leave. Google told the affected employees that it’s “keeping this matter as confidential as possible, only disclosing information on a need to know basis” in an email seen by Bloomberg. On Wednesday evening, the workers were informed they were being dismissed by the company, according to a statement from Google staff with the No Tech for Apartheid campaign.

“Physically impeding other employees’ work and preventing them from accessing our facilities is a clear violation of our policies, and completely unacceptable behavior,” Google said in a statement about the protesters. “After refusing multiple requests to leave the premises, law enforcement was engaged to remove them to ensure office safety. We have so far concluded individual investigations that resulted in the termination of employment for 28 employees, and will continue to investigate and take action as needed.”

Read More: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

The protest came a day before the Israeli government approved its five-year strategic plan to transition to the cloud under Project Nimbus and expand digital services. Israel’s Defense Ministry and military were listed in a government statement as partners in Project Nimbus, along with other government offices. A representative for Google said that the Nimbus contract is “not directed at highly sensitive, classified, or military workloads relevant to weapons or intelligence services.”

Google has long favored a culture of open debate, but employee activism in recent years has tested that commitment. Workers who organized a 2018 walkout over the company’s handling of sexual assault allegations said Google punished them for their activism. Four other workers alleged they were fired for organizing opposition to Google’s work with federal Customs and Border Protection and for other workplace advocacy.

U.S. labor law gives employees the right to engage in collective action related to working conditions. Tech workers will likely argue that this should grant them the ability to band together to object to how the tools they create are used, said John Logan, a professor of labor at San Francisco State University.

“Tech workers are not like other kinds of workers,” he said. “You can make an argument in this case that having some sort of say or control or ability to protest about how their work product is being used is actually a sort of key issue.”

Tech companies like Google have a reputation for having “more egalitarian and very cosmopolitan work cultures, but when they encountered labor activism among their own workers, they actually responded in a sort of quite draconian way,” Logan added.

Two Googlers who were involved in the protest in California told Bloomberg that a group of workers gathered on the sixth floor of Google’s Sunnyvale bureau, where Cloud Chief Executive Officer Thomas Kurian’s office is located, to show support for those who were staging the sit-in. It’s unclear how Google identified participants in the protest, as only some had their badges scanned by security personnel, and some of those who were fired were outside Google’s offices, according to the employees.

One worker said Google may have framed the move to initially place employees on leave as “confidential” to save face publicly, and argued that the protesters did not violate any company policies. The protesters left the building as soon as they were asked to and did not obstruct or disrupt others at the company, the person said.

“Every single one of the twenty-eight people whose employment was terminated was personally and definitively involved in disruptive activity inside our buildings,” a Google spokesperson said in a statement. “We carefully confirmed every single one (and then actually reconfirmed each one) during our investigation. The groups were live-streaming themselves from the physical spaces they had taken over for many hours, which did help us with our confirmation. And many employees whose work was physically disrupted submitted complaints, with details and evidence. So the claims to the contrary being made are just nonsense.”

Beyond the protest, Google has struggled with how to manage internal debate about the Middle East conflict. After the demonstration, posts on internal Google forums featured a mix of pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli sentiment, with a number of other workers saying they felt the topic was inappropriate for the workplace, a Google employee said. Moderators locked down some threads on the subject, saying prior discussions had gotten too heated, the employee added.

Despite Google’s response, employees demonstrating against Project Nimbus have seen an uptick in support since the sit-in, said one of the fired workers.

Source: Tech – TIME | 18 Apr 2024 | 6:05 pm

What’s the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

If you’ve talked to anyone invested in bitcoin lately, there’s a good chance you’ve heard about the halving. Some crypto enthusiasts intone the halving like a religious event with near mystical importance: They believe its mechanics are crucial to bitcoin’s continuing price surge. However, detractors claim that the halving is closer to a marketing gimmick.

The halving is expected to take place on April 19 or 20, depending on the current rate at which bitcoins are created. So, what is it, exactly? And is it hard-coded genius, or smoke and mirrors?

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]What is the bitcoin halving?

The halving goes all the way back to bitcoin’s origin story, born in the ashes of the 2008 financial crash. The cryptocurrency’s creator—who went by Satoshi Nakamoto, but whose real identity remains unknown—invented bitcoin the following year, and dreamed of creating an international currency that would operate outside the control of governments or central banks. Crucially, Satoshi wrote that there would only ever be 21 million bitcoin, so as to temper its inflation and potentially make each bitcoin more valuable over time.

Whereas the Federal Reserve, in contrast, can adjust the supply of dollars when they deem necessary, bitcoins would be released at a predetermined and ever-slowing pace. Satoshi determined that roughly every four years, the reward to create new bitcoins would be cut in half, in events known as “halvings.” As it became harder to create new bitcoins, each one would become rarer and more valuable, the theory went. Eventually, new bitcoin would stop being created entirely (that will likely not happen for at least another century).

Read More: Why Bitcoin Just Hit Its All-Time High

What has happened during past bitcoin halvings?

The halving is designed to make bitcoin more scarce, and ostensibly to push bitcoin’s price upward. And for the last three halvings, that’s exactly what has happened. After bitcoin’s first halving in November 2012, bitcoin’s price rose from $12.35 to $127 five months later. After the second halving in 2016, bitcoin’s price doubled to $1,280 within eight months. And between the third halving in May 2020 and March 2021, bitcoin’s price rose from $8,700 to $60,000.

But correlation does not imply causation, especially with such a small sample size. First, it’s possible that the timing of these rises was purely coincidental. It’s also possible that bitcoin’s rise has less to do with the actual mechanics of the halvings as opposed to the halvings’ narratives. With each halving, excitement grows about bitcoin’s potential, leading more people to buy in. That increase in demand causes the price to increase, which causes even more interest in a self-reinforcing cycle.

What will happen to bitcoin during this halving?

The halving will likely not cause a significant movement in price on the day it happens. Part of the economic impact of the halving has likely already occurred, with investors buying bitcoin in anticipation of the event, and the aftershocks of the halving will continue for months or years afterward, experts say.

“Given the previous history, the day-of tends to be a non-event for the price,” says Matthew Sigel, head of digital assets research at the global investment manager VanEck.

Another factor that makes it difficult to predict where bitcoin is headed post-halving is that this time, the economic circumstances surrounding it are different. It’s the first time that bitcoin has peaked before a halving, as opposed to after—last month, bitcoin rallied to an all-time high of $70,000 before dropping back down. That rally was aided by the rise of bitcoin ETFs: investment vehicles that allow mainstream institutional investors to bet on bitcoin’s price without having to actually buy bitcoin itself.

But there are some pessimists who believe that bitcoin’s big run has already happened, thanks to the ETFs—and that its price will actually decrease after the halving. A big reason for this, they believe, will be the actions of traders embarking on the strategy of “selling the news,” who cash in on their holdings in order to capitalize on a potential gold rush of interested buyers. JP Morgan predicted in February that bitcoin’s price will drop back down to $42,000 after “Bitcoin-halving-induced euphoria subsides.”

“Have we already created the buzz for bitcoin prior to halving—or is the ETF what allows Bitcoin to make similar run ups that we’ve seen in previous halvings?” says Adam Sullivan, the CEO of the bitcoin mining company Core Scientific. “We don’t have to answer that question yet.”

While many bitcoin optimists swear that its price will dramatically increase in the months following the halving, it’s important to remember that bitcoin does not always behave rationally, especially during chaotic global news events. After Iran launched a missile attack on Israel on April 13, for example, rattling the global economy, bitcoin’s price plummeted 7% in less than an hour.

Read More: A Texas Town’s Misery Underscores the Impact of Bitcoin Mines Across the U.S.

What will happen to bitcoin miners during the halving?

While determining the halving’s impact on average bitcoin investors is challenging, it seems certain that the halving will dramatically change the bitcoin mining industry. Bitcoin “miners” are essentially the network’s watchdogs, who safeguard the network from attacks, create new bitcoins, and get rewarded financially for doing so. After the halving, miners’ rewards for processing new transactions will be reduced from 6.25 bitcoin to 3.125 (about $200,000)—a significant immediate reduction of revenue.

As a result, mining will become unprofitable for many smaller operations. As they fold or sell themselves to bigger operations, like Marathon Digital Holdings Inc. or CleanSpark Inc., the industry will likely consolidate. “People are going to operate in a marginally profitable environment for as long as they possibly can,” Sullivan says. “Those are folks that will probably look to get scooped up, probably in the six-to-12 month timeframe.”

But the bitcoin mining companies that weather the storm and gain market share from those who have bowed out could reap enormous rewards, Matthew Sigel says. “Miners are always the cockroaches of the energy markets; they’re very nimble,” he says. “We think the second half of the year will be very strong for bitcoin miners, as long as the bitcoin price rallies.”

Source: Tech – TIME | 18 Apr 2024 | 3:06 am

We Need to be Ready for Biotech’s ChatGPT Moment

Imagine a world where everything from plastics to concrete is produced from biomass. Personalized cell and gene therapies prevent pandemics and treat previously incurable genetic diseases. Meat is lab-grown; enhanced nutrient grains are climate-resistant. This is what the future could look like in the years ahead.

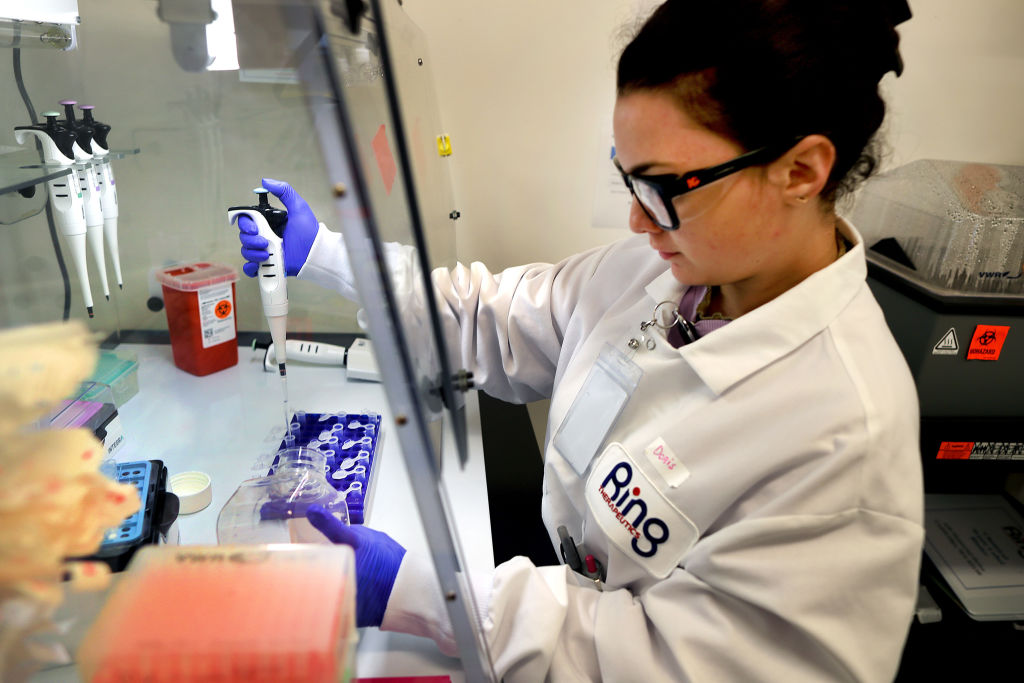

The next big game-changing revolution is in biology. It will allow us to more effectively fight disease, feed the planet, generate energy, and capture carbon. Already we’re on the cusp of these opportunities. Last year saw some important milestones: the U.S. approved the production and sale of lab-grown meat for the first time; Google DeepMind’s AI predicted structures of over 2 million new materials, which can potentially be used for chips and batteries; Casgevy became the first approved commercial gene-editing treatment using CRISPR. If I were a young person today, biology would truly be one of the most fascinating things to study.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Like the digital revolution, the biotech revolution stands to transform America’s economy as we know it—and it’s coming faster than we expect, turbocharged by AI. Recent advances in biotech are unlocking our ability to program biology just as we program computers. Just like OpenAI’s ChatGPT trains on human language input to come up with new text, AI models trained on biological sequences could design novel proteins, predict cancer growth, and create other useful consumables. In the future, AI will be able to help us run through millions of theoretical and actual biological experiments, more accurately predicting outcomes without arduous trial-and-error—vastly accelerating the rate of new discoveries.

We’re now on the verge of a “ChatGPT moment” in biology, with significant technological innovation and widespread adoption on the horizon. But how ready is America to do what it takes to bring it to fruition? I’m incredibly excited about this forthcoming breakthrough moment, but it’s paramount to ensure that it will happen on our shores. That is why I’m serving on the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology. As the Commission recently wrote in its recent interim report, “Continued U.S. leadership in biotechnology development is not guaranteed.”

America has a history of being the first mover in an emerging industry before losing its leadership when outsourcing its production to other parts of the world. This pattern has repeated itself in high-tech sectors like passenger cars, consumer electronics, solar panels, and, most notably, semiconductors. To avoid the same mistake, it’s crucial we secure a reliable supply chain domestically and internationally that covers everything from raw material extraction to data storage while we build the necessary talent pipeline. Relying on other countries for key components in biotechnology presents enormous economic and national security risks. For instance, leaving our genetic information in the hands of our adversaries could potentially aid them in developing a bioweapon used to target a specific genetic profile. President Biden’s recent executive order aims to prevent sales of such sensitive personal data to China and other adversarial countries.

An investment in both human capital and physical infrastructure will be critical to continued U.S. leadership in biotech. Such investments need not come just from the government but should also provide incentives to stimulate more private funding, as did the CHIPS and Science Act. There’s no overstating how central the bioeconomy will be to U.S. growth over the next fifty years. At present, the bioeconomy generates at least 5% of U.S. GDP; in comparison, semiconductors only constitute around 1% of U.S. GDP. By some measures, 60% of physical inputs to the global economy could be grown with biological processes—the promise of biology is vast for tackling some of humanity’s biggest challenges, including climate change.

As AI boosts our ability to engineer biology, we will need guardrails in place. While it’s easy to conjure doomsday scenarios of lone-wolf amateurs building a bioweapon from scratch right from home, studies by Rand Corporation and OpenAI have argued that current large language models like ChatGPT do not significantly increase the risk of the creation of a biological threat, as they don’t provide new information beyond what is already on the internet. And it’s also important to bear in mind that just because an AI model can design novel pathogens doesn’t mean users would have the secure wet-lab infrastructure and resources to create them.

Nonetheless, with AI tools improving in accessibility and ease of use, the biorisk landscape is ever evolving. Soon, more complex foundation models could provide malicious actors with more data, scientific expertise, and experiment troubleshooting skills, helping to suggest candidate biological agents and aid them in ordering biological parts from a diverse set of suppliers to evade screening protocols.

Organizations like the Federation of American Scientists and the Nuclear Threat Initiative have recommended structured red-teaming—actively seeking vulnerabilities to preemptively secure our biosecurity infrastructure—for current DNA sequence screening methods and evaluating the biological capabilities of AI tools. More than 90 scientists just signed a call to ensure AI develops responsibly in the field of protein design. We’ll need both standards for developing as well as requirements to implement risk assessments, as well as public-private sector collaboration in creating a robust economy of testing.

By now, most of us have likely eaten, been treated by, or worn a product created with biotech. Soon, the technology will disrupt every industry and fundamentally reshape our regular lives: new fertility treatments will transform parenthood; cellular reprogramming could start to reverse the aging process; biocomputing will power the computers of tomorrow. Standing on the brink of these innovations, we as a country have the unique chance to drive how biotech unfolds, realize its immense benefits, and shape the norms for responsible innovation—before other countries race ahead.

Source: Tech – TIME | 17 Apr 2024 | 8:20 am

The Economist Breaking Ranks to Warn of AI’s Transformative Power

Technologists tend to predict that the economic impacts of their creations will be unprecedented—and this is especially true when it comes to artificial intelligence. Last year, Elon Musk predicted that continued advances in AI would render human labor obsolete. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has written that AI will inevitably continue the shift in economic power from labor to capital and create “phenomenal wealth.” Jensen Huang, CEO of semiconductor design firm Nvidia, has compared AI’s development and deployment to a “new industrial revolution.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]But while the technologists are bullish on the economic impacts of AI, members of that other technocratic priesthood with profound influence over public life—the economists—are not. Even if technologists create the powerful AI systems that they claim they soon will, the economic impacts of those systems are likely to be underwhelming, say many economists. According to Tyler Cowen, an economics professor at George Mason University, AI will “boost the annual US growth rate by one-quarter to one-half of a percentage point.” Economics Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman has argued that “history suggests that large economic effects from A.I. will take longer to materialize than many people currently seem to expect.” David Autor, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has written that the “industrialized world is awash in jobs, and it’s going to stay that way.”

As an economics professor at the University of Virginia with affiliations to some of the profession’s most reputable institutions, Anton Korinek is a certified member of the priesthood. The 46-year-old, however, has broken rank. He uses the methods of his discipline to model what would happen if AI developed as many technologists say it might—which is to say that AI systems are likely to outperform humans at any task by the end of the decade. In the sterile lexicon of academic economics, he paints an alarming picture of a near future in which humans cease to play a role in the economy, and inequality soars.

If “the complexity of tasks that humans can perform is bounded and full automation is reached, then wages collapse,” write Korinek and one of his Ph.D. students, Donghyun Suh, in a recent paper. In other words, if there’s a limit to how complex the tasks humans can do are, and machines become advanced enough to fully automate all those tasks, then wages could drastically fall as human labor is no longer needed, leaving anyone who doesn’t share in the resources that accrue to AI systems and their owners to starve.

Economists have spent the last 200 years explaining to the uninitiated that the lump of labor fallacy—the idea that there is a fixed number of jobs and automation of any of those jobs will create permanent unemployment—is wrong, says Korinek. “In some ways, that’s our professional baggage,” he says. “We’ve spent so much time fighting a false narrative, that it’s difficult to pivot when the facts really do change, and see that this situation may indeed be different.”

“The scariest part about it is that the technological predictions that I use as inputs are what people like Sam Altman or [Anthropic CEO] Dario Amodei are freely preaching in public everywhere,” says Korinek. “I’m not a technology expert, and I don’t have any special insight or knowledge to these issues. I’m just taking what they’re saying seriously and asking: what would it actually mean for the economy, and for jobs, and for wages? It would be completely disruptive.”

Korinek’s father, a primary care physician, instilled in him a passion for understanding the brain. As a teen in Austria, Korinek became fascinated with neuroscience and learnt to program. At college, he took a course on neural networks—the brain-inspired AI systems that have since become the most popular and powerful in the industry. “It was intriguing, but at the same time, boring, because the technology just wasn’t very powerful using the tools that we had back then,” he recalls.

As Korinek was finishing college in the late 1990s, the Asian financial crisis hit. The 1997 crash, precipitated by a foreign exchange crisis in Thailand, followed many other episodes of acute financial distress in emerging markets. Korinek decided to do a Ph.D. on financial crises and how to prevent them. Fortunately for him—although less fortunately for everyone else—the global financial crisis struck in 2008, a year after he finished his thesis. His expertise was in demand, and his career took off.

As an academic economist, he watched from the sidelines as AI researchers made breakthrough after breakthrough; scanning newspapers, listening to radio programs, and reading books on AI. In the early 2010s, as AI systems began to outdo humans at tasks such as image recognition, he began to believe that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—the term used to describe a yet to be built AI system that could do any task a human could—might be developed alarmingly soon. But it took the birth of his first child in 2015 to get him off the sidelines. “There is really something happening, and it’s happening faster than I thought in the 1990s,” he recalls thinking. “This is really going to be relevant for my daughter’s life path.”

Read More: 4 Charts That Show Why AI Progress Is Unlikely to Slow Down

Using the methods of economics, Korinek has sought to understand how future AI systems might affect economic growth, wages, and employment, how the inequality created by AI could imperil democracy, and how policymakers should respond to economic issues posed by AI. For years, working on the economics of AGI was a fringe pursuit. Economics Ph.D. students would tell Korinek that they would like to work on the questions he was beginning to study, but they felt they needed to stick to more mainstream topics if they wanted to get a job. Despite having been awarded tenure in 2018 and thus being insulated from the pressures of the academic job market, Korinek felt discouraged at times. “Researchers are still also social creatures,” he says. “If you only face skepticism towards your work, it makes it much, much harder to push forward a research agenda, because you start questioning yourself.”

Up until OpenAI released the wildly popular chatbot, ChatGPT, in November 2022, Korinek says research on the economics of AGI was a fringe pursuit. Now, it’s “on an exponential growth path,” says Korinek.

Many economists still, quite reasonably, dismiss the possibility of AGI being developed in the coming decades. Skeptics point to the many ways in which current systems fall short of human abilities, the potential roadblocks to continued AI progress such as a shortfall in data to train larger models, and the history of technologists making overconfident predictions. A paper published in February by economists in Portugal and Germany sets aside AGI as “science fiction,” and thus argues that AI is unlikely to cause explosive economic growth.

Read More: When Might AI Outsmart Us? It Depends Who You Ask

“Two years ago, that was absolutely commonplace—that was the median reaction,” says Korinek. But more people are starting to entertain the possibility of AGI being developed, and those who continue to dismiss the possibility are providing solid arguments for their position rather than dismissing it out of hand. “People are, in other words, engaging very seriously in the debate,” he says approvingly.

Other economists are open to the possibility of AGI being developed in the foreseeable future, but argue that this still wouldn’t precipitate a collapse in employment. Often, they put the disagreement with those who do think the development of AGI might cause these things down to the other side’s economic illiteracy.

For example, in March, economist Noah Smith argued in a blog post that was picked up by the New York Times that well-paid jobs will be plentiful, even after AI can outperform humans at any task. This is, Smith forbearingly explains, because AI systems and humans can each specialize in the tasks where their relative advantage is greatest—an economic idea known as comparative advantage—and then trade with each other. When “most people hear the term “comparative advantage” for the first time, they immediately think of the wrong thing,” writes Smith.

But Korinek is hardly economically illiterate. “I claim to say I do understand comparative advantage,” he says with a grin. Korinkek’s models, which account for comparative advantage, still don’t paint an optimistic picture for humans in a world where AI systems can do any task a human can. “The theory of comparative advantage tells us that there is scope for gains from trade,” says Korinek. “But the big problem is, it does not tell us that the terms of that trade will be sufficient for humans to make a decent living, or even for humans to cover their subsistence cost.”

Later in his blog post, Smith does go on to say that government intervention, in the form of a tax on AI or by setting limits on the amount of energy AI systems can use, could be required to ensure that humans can earn enough to survive if AI can outperform them at any task. But while Smith is confident that governments will take these steps if they prove necessary, Korinek is less sure.

“The economists are slowly starting to take the potential job disruption from AI more seriously,” he says. “Policymakers are not quite there yet—that’s my concern. I’m nervous about this, because we may not have all that much time.”

Korinek does not share the certitude with which many technologists predict the imminent development of AGI. But given the potential implications of such a technology, society must prepare, he says.

“It may take many more decades until we come even close to replicating the things that the human brain does,” he says. “But I think there’s also a sufficiently high chance that it really won’t take that long and this is going to happen really quickly, and that it will turn our society upside down.”

More From TIME

Source: Tech – TIME | 17 Apr 2024 | 3:47 am

Exclusive: Tech Companies Are Failing to Keep Elections Safe, Rights Groups Say

A quarter of the way into the most consequential election year in living memory, tech companies are failing their biggest test. Such is the charge that has been leveled by at least 160 rights groups across 55 countries, which are collectively calling on tech platforms to urgently adopt greater measures to safeguard people and elections amid rampant online disinformation and hate speech.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]“Despite our and many others’ engagement, tech companies have failed to implement adequate measures to protect people and democratic processes from tech harms that include disinformation, hate speech, and influence operations that ruin lives and undermine democratic integrity,” reads the organizations’ joint letter, shared exclusively with TIME by the Global Coalition for Tech Justice, a consortium of civil society groups, activists, and experts. “In fact, tech platforms have apparently reduced their investments in platform safety and have restricted data access, even as they continue to profit from hate-filled ads and disinformation.”

In July, the coalition reached out to leading tech companies, among them Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram), Google (which owns YouTube), TikTok, and X (formerly known as Twitter), and asked them to establish transparent, country-specific plans for the upcoming election year, in which more than half of the world’s population would be going to the polls across some 65 countries. But those calls were largely ignored, says Mona Shtaya, the campaigns and partnerships manager at Digital Action, the convenor of the Global Coalition for Tech Justice. She notes that while many of these firms have published press releases on their approach to the election year, they are often vague and lack country-specific details, such as the number of content moderators per country, language, and dialect. Crucially, some appeared to disproportionately focus on the U.S. elections.

“Because they are legally and politically accountable in the U.S., they are taking more strict measures to protect people and their democratic rights in the U.S.,” says Shtaya, who is also the Corporate Engagement Lead at Digital Action. “But in the rest of the world, there are different contexts that could lead to the spread of disinformation, misinformation, hateful content, gender-based violence, or smear campaigns against certain political parties or even vulnerable communities.”

When reached for comment, TikTok pointed TIME to a statement on its plans to protect election integrity, as well as separate posts on its plans for the elections in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Taiwan, Pakistan, the European Parliament, the U.S., and the U.K. Google similarly pointed to its published statements on the upcoming U.S. election, as well as the forthcoming contests in India and Europe. Meta noted that it has “provided extensive public information about our preparations for elections in major countries around the world,” including in statements on forthcoming elections in India, the E.U., Brazil, and South Africa.

X did not respond to requests for comment.

Tech platforms have long had a reputation for underinvesting in content moderation in non-English languages, sometimes to dangerous effect. In India, which kicks off its national election this week, anti-Muslim hate speech under the country’s Hindu nationalist government has given way to rising communal violence. The risks of such violence notwithstanding, observers warn that anti-Muslim and misogynistic hate speech continue to run rampant on social tech platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. In South Africa, which goes to the polls next month, online xenophobia has manifested into real-life violence targeting migrant workers, asylum seekers, and refugees—something that observers say social media platforms have done little to curb. Indeed, in a joint investigation conducted last year by the Cape Town-based human-rights organization Legal Resources Centre and the international NGO Global Witness, 10 non-English advertisements were approved by Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube despite the ads violating the platforms’ own policies on hate speech.

Rather than invest in more extensive content moderation, the Global Coalition for Tech Justice contends that tech platforms are doing just the opposite. “In the past year, Meta, Twitter, and YouTube have collectively removed 17 policies aimed at guarding against hate speech and disinformation,” Shtaya says, referencing a recent report by the non-profit media watchdog Free Press. She added that all three companies have had layoffs, with some directly affecting teams dedicated to content moderation and trust and safety.

Just last month, Meta announced its decision to shut down CrowdTangle, an analytics tool widely used by journalists and researchers to track misinformation and other viral content on Facebook and Instagram. It will cease to function on Aug. 14, 2024, less than three months before the U.S. presidential election. The Mozilla Foundation and 140 other civil society organizations (including several that signed onto the Global Coalition for Tech Justice letter) condemned the move, which it deemed “a direct threat to our ability to safeguard the integrity of elections.”

Read More: Inside Facebook’s African Sweatshop

Perhaps the biggest concern surrounding this year’s elections is the threat posed by AI-generated disinformation, which has already proven capable of producing fake images, audio, and video with alarming believability. Political deepfakes have already cropped up in elections in Slovakia (where AI-generated audio recordings purported to show a top candidate boasting about rigging the election, which he would go on to lose) and Pakistan (where a video of a candidate was altered to tell voters to boycott the vote). That they’ll feature in the upcoming U.S. presidential contest is almost a given: Last year, former President and presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump shared a manipulated video using AI voice-cloning of CNN host Anderson Cooper. More recently, a robocall purportedly recorded by President Biden (it was, in fact, an AI-generated impersonation of him) attempted to discourage voters from participating in the New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary just days leading up to the vote. (A political consultant who confessed to being behind the hoax claimed he was trying to warn the country about the perils of AI.)

This isn’t the first time tech companies have been called out for their lack of preparedness. Just last week, a coalition of more than 200 civil-society organizations, researchers, and journalists sent a letter to the top of executives of a dozen social media platforms calling on them to take “swift action” to combat AI-driven disinformation and to reinforce content moderation, civil-society oversight tools, and other election integrity policies. Until these platforms respond to such calls, it’s unlikely to be the last.

Source: Tech – TIME | 17 Apr 2024 | 12:02 am

How Virtual Reality Could Transform Architecture

I’m standing over a table, looking at a 3D architectural model of a room. Then I hit a button, and suddenly I’m inside the model itself. I can walk around, get a feel for the space, see how the plumbing and lighting systems intersect, and flag any potential problems for the room’s designers to tweak.

Of course, I haven’t actually shrunk into the table: I’m wearing a headset in an architectural virtual reality app. Over the past few years, more and more architects have started to incorporate immersive VR tools in the process of designing buildings. VR, they say, helps them understand spaces better, facilitate better collaboration, and catch errors they might not have otherwise. These architects hope that as VR technology improves and becomes more commonplace, it could fundamentally transform the way that they approach their jobs, and lead to more efficient and effective design.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]But there are also architects who feel that the current spate of VR products does not yet live up to the hype put forth by technologists. “We have questions we can already very effectively answer in 2D on a screen,” says Jacob Morse, the managing director at the architecture and design firm Geniant. “Putting it in goggles is just a gimmick.”

Building from scratch with the headset on

For decades, architects have designed buildings starting with 2D blueprints, which require technical knowledge to fully comprehend. When it comes to design, working in two dimensions is “not a natural experience,” says Jon Matalucci, a virtual design and construction manager at Stantec, a global design and engineering firm. “We experience things in 3D, and there’s a loss in translation.”

Prior to a few years ago, using VR was prohibitively expensive for many architects, and it took far too long for design programs to render 3D spaces. But upgrades in both hardware and software mean that many architecture firms now own VR headsets, whether it be the Meta Quest or the Google Cardboard. Design tools like Revit and Rhino turn blueprints into 3D digital models. And in programs like Enscape and Twinmotion, architects can walk into spaces they’ve designed within minutes of creating them.

Read More: The Biggest Decider of the Vision Pro’s Success Is Out of Apple’s Hands

The architect Danish Kurani, who runs his own design studio, has been using VR tools for seven years. Early on in the process of designing a room or building, Kurani puts on a headset to view proposals created by architects on his team and talk through different options. When they’ve finished their preliminary designs, he then gives his clients guided tours to get them excited and to solicit feedback. During our interview over Google Meets, Kurani takes me through a virtual rendering of a nonprofit entrepreneurship center for kids that he designed in Baltimore, its rustic brick walls lined with 3D printers and other tools.

“As we walk around, I’ll ask them questions like, ‘Is this enough space in front of the laser cutter?’” Kurani says. “They’re really appreciative of being able to see it this way as opposed to looking at abstract black and white lines on a floor plan. They’re really able to immerse themselves.”

Kurani says that VR allows him to detect subtle design problems that he might not have noticed on a screen. Walking around a classroom in VR with an audiovisual engineer, for example, lets them figure out the best placements for cameras so that remote teachers can clearly see their students and vice versa. Being in VR also allows Kurani to see if an exit sign might block the view of a student sitting in a back row who is trying to see a presentation on a high projector screen.

Matalucci, at Stantec, says that his company now has the ability to “put a headset on every desk.” The company is a customer of the design software powerhouse Autodesk, and its employees were among the first users of Autodesk’s Workshop XR, a 3D design review software which was announced in November and is available in beta. The software allows architects to virtually step into their creations at a 1:1 scale. One of the projects that Stantec recently used Workshop XR for was a hospital in rural New Mexico. Matalucci says that VR is especially useful in designing healthcare buildings because of all of the overlapping systems required in them, from process piping to oxygen to electrical.

VR helped Stantec’s designers receive feedback from clients and make tweaks in real time, Matalucci says. They even sent VR demos to night-shift nurses to see how they felt moving around the virtual hospital’s halls. “We were populating the facility with features based on their requests. At any moment when they wanted to see where we were in the process, they were able to put on their headset and go to remote rural New Mexico, giving them visibility into a very complex process,” he says. “As a result, we were getting answers to questions that we didn’t even think to ask.”

Read More: Cell Phone Pouches Promise to Improve Focus at School. Kids Aren’t Convinced

Experiencing Workshop XR myself, via a Meta Quest 3 headset,is a surreal experience. With the help of Autodesk XR product marketing manager Austin Baker, I teleport in and out of architectural models and fly around a Boston municipal building, seeing how its grand staircase unfolds into a large atrium. I can trace how sunlight and shadows move across the floor. Theoretically, dozens of different people working on various aspects of the project could convene here, hashing out decisions in real time before a single brick is laid.

“What would have been dozens of back and forth emails, Zoom calls, and trying to share renderings of our 2D data is now a 15-minute intuitive walkthrough, where we have all the data at our fingertips,” Baker tells me, his avatar floating next to mine. “We’re able to spot issues that could cost millions of dollars downstream.”

Steffen Riegas, a partner and lead of digital practice at the Basel-based firm Herzog & de Meuron, says that VR has been especially useful in designing and reviewing complex interior situations like staircases. “It’s really hard to communicate those narrow vertical spaces and depth in two dimensions; it’s almost impossible,” he says. “VR solves that.”

Herzog & de Meuron has incorporated VR and XR (extended reality) tools into many parts of its practice. The firm’s partners and project teams sometimes don headsets to make design decisions. And the company’s architects even took Microsoft’s HoloLens—a mixed reality headset that allows users to project virtual objects onto the real world—onto an actual project site in Basel, to see how their new building designs might look next to the physical ones already there. “If you want to get an impression of what a site will feel like, it’s difficult to experience or illustrate that with drawings,” Riegas says. “But with XR, you can walk to the other side of the block and see how a new building will look from different perspectives.”

The limitations of current VR tools

But the current VR tools are not universally hailed by architects or other professionals in the design space. Kurani says that he’s encountered general contractors and subcontractors who are resistant to using these new tools due to the learning curve, which makes integrating them into processes less worthwhile. “If subcontractors can’t use the technology, then you’re wasting time and energy,” he says.

Jacob Morse, at Geniant, says that from what he’s seen, many architects use VR goggles only as a marketing tool, as opposed to integrating it into their design processes. “I’ve yet to see the compelling use cases, apart from selling and presenting, that really push the field of architecture forward,” he says. “At large, it hasn’t unlocked completely new insights and new solutions that we can’t accomplish in desktop computer programs.”

However, Morse does hold out hope that as headsets and software and software improve, VR could allow him and other architects to approach design as a more iterative process, using it to research, prototype, and test how people respond to slight tweaks in their virtual environments. David Dewane, the chief experience officer of physical space at Geniant, hopes that VR could also be used in education: to allow students to virtually accompany an elite design team from conception to construction, or to study the most famous buildings in the world up close.

“Any architecture student should be able to go into the library and not just pull out a book on the Barcelona Pavilion, but go to the Barcelona Pavilion,” he says. “We are ready for that now. But nobody in the market has gone out and built it yet.”

Source: Tech – TIME | 16 Apr 2024 | 11:00 pm

U.K. to Criminalize Creating Sexually Explicit Deepfake Images

The U.K. will criminalize the creation of sexually explicit deepfake images as part of plans to tackle violence against women.

People convicted of creating such deepfakes without consent, even if they don’t intend to share the images, will face prosecution and an unlimited fine under a new law, the Ministry of Justice said in a statement. Sharing the images could also result in jail.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Rapid developments in artificial intelligence have led to the rise of the creation and dissemination of deepfake images and videos. The U.K. has classified violence against women and girls as a national threat, which means the police must prioritize tackling it, and this law is designed to help them clamp down on a practice that is increasingly being used to humiliate or distress victims.

Read More: As Tech CEOs Are Grilled Over Child Safety Online, AI Is Complicating the Issue

“This new offence sends a crystal clear message that making this material is immoral, often misogynistic, and a crime,” Laura Farris, minister for victims and safeguarding, said in a statement.

The government is also introducing new criminal offenses for people who take or record real intimate images without consent, or install equipment to enable someone to do so. A new statutory aggravating factor will be brought in for offenders who cause death through abusive, degrading or dangerous sexual behavior.

Source: Tech – TIME | 16 Apr 2024 | 2:05 pm

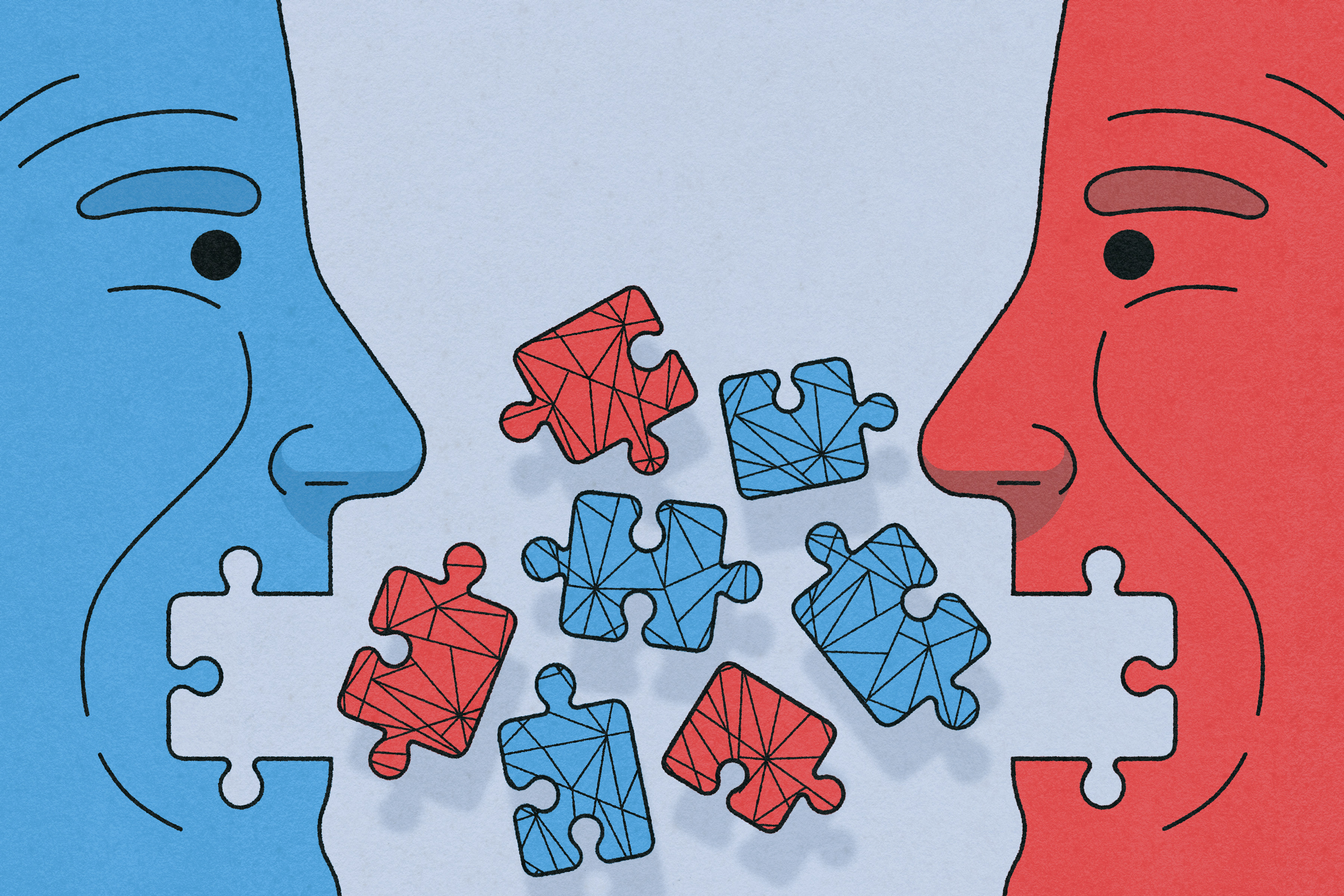

The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

In the 1990s and early 2000s, technologists made the world a grand promise: new communications technologies would strengthen democracy, undermine authoritarianism, and lead to a new era of human flourishing. But today, few people would agree that the internet has lived up to that lofty goal.

Today, on social media platforms, content tends to be ranked by how much engagement it receives. Over the last two decades politics, the media, and culture have all been reshaped to meet a single, overriding incentive: posts that provoke an emotional response often rise to the top.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Efforts to improve the health of online spaces have long focused on content moderation, the practice of detecting and removing bad content. Tech companies hired workers and built AI to identify hate speech, incitement to violence, and harassment. That worked imperfectly, but it stopped the worst toxicity from flooding our feeds.

There was one problem: while these AIs helped remove the bad, they didn’t elevate the good. “Do you see an internet that is working, where we are having conversations that are healthy or productive?” asks Yasmin Green, the CEO of Google’s Jigsaw unit, which was founded in 2010 with a remit to address threats to open societies. “No. You see an internet that is driving us further and further apart.”

What if there were another way?

Jigsaw believes it has found one. On Monday, the Google subsidiary revealed a new set of AI tools, or classifiers, that can score posts based on the likelihood that they contain good content: Is a post nuanced? Does it contain evidence-based reasoning? Does it share a personal story, or foster human compassion? By returning a numerical score (from 0 to 1) representing the likelihood of a post containing each of those virtues and others, these new AI tools could allow the designers of online spaces to rank posts in a new way. Instead of posts that receive the most likes or comments rising to the top, platforms could—in an effort to foster a better community—choose to put the most nuanced comments, or the most compassionate ones, first.

Read More: How Americans Can Tackle Political Division Together

The breakthrough was made possible by recent advances in large language models (LLMs), the type of AI that underpins chatbots like ChatGPT. In the past, even training an AI to detect simple forms of toxicity, like whether a post was racist, required millions of labeled examples. Those older forms of AI were often brittle and ineffectual, not to mention expensive to develop. But the new generation of LLMs can identify even complex linguistic concepts out of the box, and calibrating them to perform specific tasks is far cheaper than it used to be. Jigsaw’s new classifiers can identify “attributes” like whether a post contains a personal story, curiosity, nuance, compassion, reasoning, affinity, or respect. “It’s starting to become feasible to talk about something like building a classifier for compassion, or curiosity, or nuance,” says Jonathan Stray, a senior scientist at the Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI. “These fuzzy, contextual, know-it-when-I-see-it kind of concepts— we’re getting much better at detecting those.”

This new ability could be a watershed for the internet. Green, and a growing chorus of academics who study the effects of social media on public discourse, argue that content moderation is “necessary but not sufficient” to make the internet a better place. Finding a way to boost positive content, they say, could have cascading positive effects both at the personal level—our relationships with each other—but also at the scale of society. “By changing the way that content is ranked, if you can do it in a broad enough way, you might be able to change the media economics of the entire system,” says Stray, who did not work on the Jigsaw project. “If enough of the algorithmic distribution channels disfavored divisive rhetoric, it just wouldn’t be worth it to produce it any more.”

One morning in late March, Tin Acosta joins a video call from Jigsaw’s offices in New York City. On the conference room wall behind her, there is a large photograph from the 2003 Rose Revolution in Georgia, when peaceful protestors toppled the country’s Soviet-era government. Other rooms have similar photos of people in Syria, Iran, Cuba and North Korea “using tech and their voices to secure their freedom,” Jigsaw’s press officer, who is also in the room, tells me. The photos are intended as a reminder of Jigsaw’s mission to use technology as a force for good, and its duty to serve people in both democracies and repressive societies.

On her laptop, Acosta fires up a demonstration of Jigsaw’s new classifiers. Using a database of 380 comments from a recent Reddit thread, the Jigsaw senior product manager begins to demonstrate how ranking the posts using different classifiers would change the sorts of comments that rise to the top. The thread’s original poster had asked for life-affirming movie recommendations. Sorted by the default ranking on Reddit—posts that have received the most upvotes—the top comments are short, and contain little beyond the titles of popular movies. Then Acosta clicks a drop-down menu, and selects Jigsaw’s reasoning classifier. The posts reshuffle. Now, the top comments are more detailed. “You start to see people being really thoughtful about their responses,” Acosta says. “Here’s somebody talking about School of Rock—not just the content of the plot, but also the ways in which the movie has changed his life and made him fall in love with music.” (TIME agreed not to quote directly from the comments, which Jigsaw said were used for demonstrative purposes only and had not been used to train its AI models.)

Acosta chooses another classifier, one of her favorites: whether a post contains a personal story. The top comment is now from a user describing how, under both a heavy blanket and the influence of drugs, they had ugly-cried so hard at Ke Huy Quan’s monologue in Everything Everywhere All at Once that they’d had to pause the movie multiple times. Another top comment describes how a movie trailer had inspired them to quit a job they were miserable with. Another tells the story of how a movie reminded them of their sister, who had died 10 years earlier. “This is a really great way to look through a conversation and understand it a little better than [ranking by] engagement or recency,” Acosta says.

For the classifiers to have an impact on the wider internet, they would require buy-in from the biggest tech companies, which are all locked in a zero-sum competition for our attention. Even though they were developed inside Google, the tech giant has no plans to start using them to help rank its YouTube comments, Green says. Instead, Jigsaw is making the tools freely available for independent developers, in the hopes that smaller online spaces, like message boards and newspaper comment sections, will build up an evidence base that the new forms of ranking are popular with users.

There are some reasons to be skeptical. For all its flaws, ranking by engagement is egalitarian. Popular posts get amplified regardless of their content, and in this way social media has allowed marginalized groups to gain a voice long denied to them by traditional media. Introducing AI into the mix could threaten this state of affairs. A wide body of research shows that LLMs have plenty of ingrained biases; if applied too hastily, Jigsaw’s classifiers might end up boosting voices that are already prominent online, thus further marginalizing those that aren’t. The classifiers could also exacerbate the problem of AI-generated content flooding the internet, by providing spammers with an easy recipe for AI-generated content that’s likely to get amplified. Even if Jigsaw evades those problems, tinkering with online speech has become a political minefield. Both conservatives and liberals are convinced their posts are being censored; meanwhile, tech companies are under fire for making unaccountable decisions that affect the global public square. Jigsaw argues that its new tools may allow tech platforms to rely less on the controversial practice of content moderation. But there’s no getting away from the fact that changing what kind of speech gets rewarded online will always have political opponents.

Still, academics say that given a chance, Jigsaw’s new AI tools could result in a paradigm shift for social media. Elevating more desirable forms of online speech could create new incentives for more positive online—and possibly offline—social norms. If a platform amplifies toxic comments, “then people get the signal they should do terrible things,” says Ravi Iyer, a technologist at the University of Southern California who helps run the nonprofit Psychology of Technology Research Network. “If the top comments are informative and useful, then people follow the norm and create more informative and useful comments.”

The new algorithms have come a long way from Jigsaw’s earlier work. In 2017, the Google unit released Perspective API, an algorithm for detecting toxicity. The free tool was widely used, including by the New York Times, to downrank or remove negative comments under articles. But experimenting with the tool, which is still available online, reveals the ways that AI tools can carry hidden biases. “You’re a f-cking hypocrite” is, according to the classifier, 96% likely to be a toxic phrase. But many other hateful phrases, according to the tool, are likely to be non-toxic, including the neo-Nazi slogan “Jews will not replace us” (41%) and transphobic language like “trans women are men” (36%). The tool breaks when confronted with a slur that is commonly directed at South Asians in the U.K. and Canada, returning the error message: “We don’t yet support that language, but we’re working on it!”

To be sure, 2017 was a very different era for AI. Jigsaw has made efforts to mitigate biases in its new classifiers, which are unlikely to make such basic errors. Its team tested the new classifiers on a set of comments that were identical except for the names of different identity groups, and said it found no hint of bias. Still, the patchy effectiveness of the older Perspective API serves as a reminder of the pitfalls of relying on AI to make value judgments about language. Even today’s powerful LLMs are not free from bias, and their fluency can often conceal their limitations. They can discriminate against African American English; they function poorly in some non-English languages; and they can treat equally-capable job candidates differently based on their names alone. More work will be required to ensure Jigsaw’s new AIs don’t have less visible forms of bias. “Of course, there are things that you have to watch out for,” says Iyer, who did not work on the Jigsaw project. “How do we make sure that [each classifier] captures the diversity of ways that people express these concepts?”

In a paper published earlier this month, Acosta and her colleagues set out to test how readers would respond to a list of comments ranked using Jigsaw’s new classifiers, compared to comments sorted by recency. They found that readers preferred the comments sorted by the classifiers, finding them to be more informative, respectful, trustworthy, and interesting. But they also found that ranking comments by just one classifier on its own, like reasoning, could put users off. In its press release launching the classifiers on Monday, Jigsaw says it intends for its tools to be mixed and matched. That’s possible because all they do is return scores between zero and one—so it’s possible to write a formula that combines several scores together into a single number, and use that number as a ranking signal. Web developers could choose to rank comments using a carefully-calibrated mixture of compassion, respect, and curiosity, for example. They could also throw engagement into the mix as well – to make sure that posts that receive lots of likes still get boosted too.

Just as removing negative content from the internet has received its fair share of pushback, boosting certain forms of “desirable” content is likely to prompt complaints that tech companies are putting their thumbs on the political scales. Jigsaw is quick to point out that its classifiers are not only apolitical, but also propose to boost types of content that few people would take issue with. In tests, Jigsaw found the tools did not disproportionately boost comments that were seen by users as unfavorable to Republicans or Democrats. “We have a track record of delivering a product that’s useful for publishers across the political spectrum,” Green says. “The emphasis is on opening up conversations.” Still, the question of power remains: who gets to decide which kinds of content are desirable? Jigsaw’s hope is that by releasing the technology publicly, different online spaces can each choose what works for them—thus avoiding any one hegemonic platform taking that decision on behalf of the entire internet.

For Stray, the Berkeley scientist, there is a tantalizing prospect to an internet where positive content gets boosted. Many people, he says, think of online misinformation as leading to polarization. And it can. “But it also works the other way around,” he says. The demand for low-quality information arises, at least in part, because people are already polarized. If the tools result in people becoming less polarized, “then that should actually change the demand-side for certain types of lower quality content.” It’s hypothetical, he cautions, but it could lead to a virtuous circle, where declining demand for misinformation feeds a declining supply.

Why would platforms agree to implement these changes? Almost by definition, ranking by engagement is the most effective way to keep users onsite, thus keeping eyeballs on the ads that drive up revenue. For the big platforms, that means both the continued flow of profits, and the fact that users aren’t spending time with a competitor’s app. Replacing engagement-based ranking with something less engaging seems like a tough ask for companies already battling to keep their users’ attention.

That’s true, Stray says. But, he notes that there are different forms of engagement. There’s short-term engagement, which is easy for platforms to optimize for: is a tweak to a platform likely to make users spend more time scrolling during the next hour? Platforms can and do make changes to boost their short-term engagement, Stray says—but those kinds of changes often mean boosting low-quality, engagement-bait types of content, which tend to put users off in the long term.

The alternative is long-term engagement. How might a change to a platform influence a user’s likelihood of spending more time scrolling during the next three months? Long-term engagement is healthier, but far harder to optimize for, because it’s harder to isolate the connection between cause and effect. Many different factors are acting upon the user at the same time. Large platforms want users to be returning over the long term, Stray says, and for them to cultivate healthy relationships with their products. But it’s difficult to measure, so optimizing for short-term engagement is often an easier choice.

Jigsaw’s new algorithms could change that calculus. “The hope is, if we get better at building products that people want to use in the long run, that will offset the race to the bottom,” Stray says. “At least somewhat.”

More From TIME

Source: Tech – TIME | 16 Apr 2024 | 6:00 am